Intro#

Reusing functions is one of our goals as developers, and React makes it easy to create reusable components. Reusable components can be shared across multiple domains of your application to avoid duplication. We will cover the following topics:

-

How components communicate with each other using props and children

-

The container and presentational patterns and how they can make our code more maintainable

-

What higher-order components (HOCs) are and how, thanks to them, we can structure our applications in a better way

-

What the function of the child component pattern is and what its benefits are

Basic Component Relationship#

Lets start with a code example:

// inside App.js

export default function App(){

const [counter, setCounter] = useState( 0 );

const incrementCounter = () => setCounter( prevValue => prevValue + 1 )

return (

<div className="m-2 text-center">

<Message theme="primary" message={`Counter: ${this.state.counter}`}/>

<ActionButton theme="secondary" text="Increment"

callback={this.incrementCounter}/>

</div>

)

}

//inside Message.js

export function Message( { theme, message } ){

return (

<div className={`h5 bg-${theme} text-white p-2`}>

{message}

</div>

)

}

//inside ActionButton.js

export const ActionButton = ( { theme, text, callback } ) => {

return (

<button className={` btn btn-${theme} m-2`} onClick={callback}>

{text}

</button>

)

}

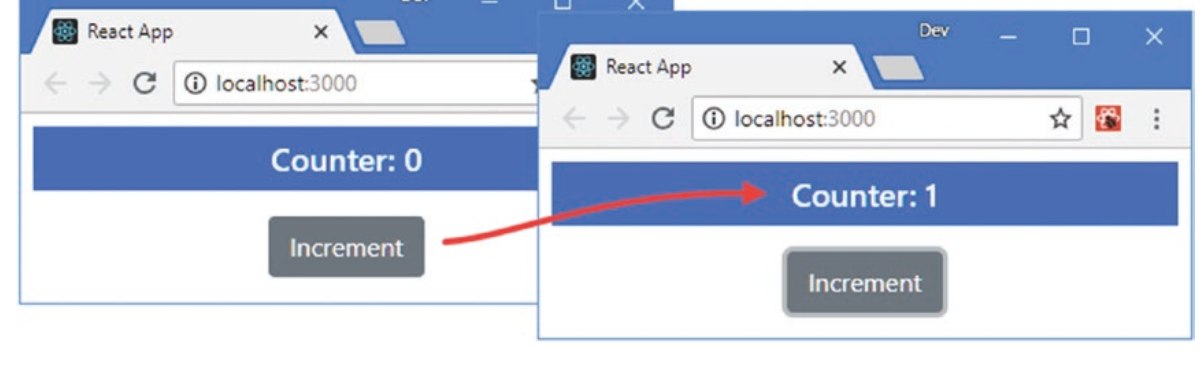

Which give use this output:

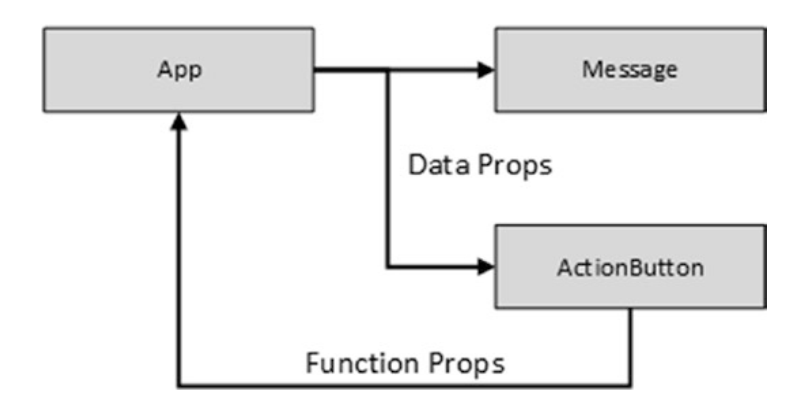

The above components are very simple, But they illustrate the basic relationship that underpins React philosophy: Parent component( owners ) configure children with data props and receive notification through function props, Which triggers an update process in case of state data change.

This pattern is easy to understand in a simple example, but its use in more complex situations can be less obvious, and it can be hard to know how to locate and distribute the state data, props, and callbacks without duplicating code and data.

Using the Children Prop#

React provides a special children prop that is used when a component needs to display content provided by its parent (

owner) component but doesn’t know what that content will be in advance. In the React documentation, it is described as

opaque because it is a property that does not tell you anything about the value it contains. This is a useful way of

reducing duplication of the component by standardizing features in that component that can be reused across an

application.

So that means Components can also be defined with nested components inside them, and they can access those nested

components using the children prop. To demonstrate, let create a ThemeSelector component that handles local theming

for the above example.

//inside ThemeSelector.js

export function ThemeSelector( { children } ){

return (

<div className="bg-dark p-2">

<div className="bg-info p-2">

{children} // render whatever component passed as child

</div>

</div>

)

}

// inside App.js, we pass those same component to `ThemeSelector`

import { ThemeSelector } from "./ThemeSelector";

export default function App(){

....

return(

<div className="m-2 text-center">

<ThemeSelector>

<Message theme="primary" message={`Counter: ${counter}`}/>

<Button theme="secondary" text="Increment"

callback={incrementCounter}/>

</ThemeSelector>

</div>

)

}

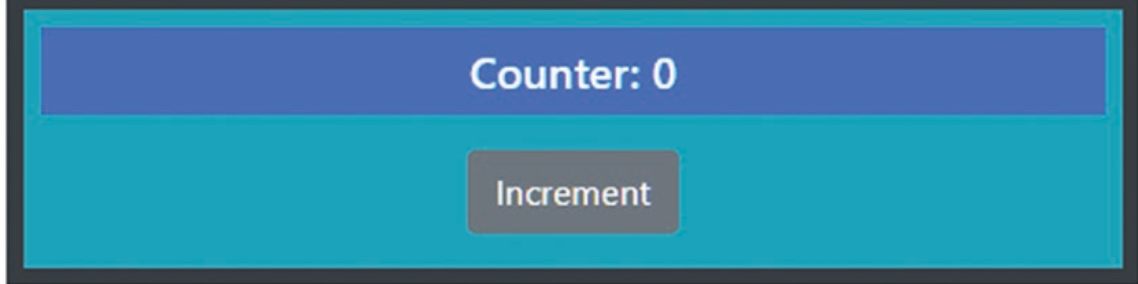

The App component provides content for the ThemeSelector component by defining elements between its start and end

tags. In this case Message and ActionButton components. When React processes the content rendered by the App

component, the content between the ThemeSelector tags is assigned to the children prop, The ThemeSelector

use bg-dark Bootstrap background class producing the result shown:

Adding Props to components received through the children prop.#

This is not an ideal or recommended way to pass props to child components, I mentioned it in case you got stuck working

with the children prop only and also to let you know about React Top-Level APIs methods.

As we said earlier component can’t manipulate the content it receives from the parent directly, so to provide the

components received through the children prop with additional data or functions, the React.Children.map method is used

in conjunction with the React.cloneElement method to duplicate the child components and assign additional props. Those

are React Top-Level APIs methods.

Let's add a select html element to the content rendered by the ThemeSelector that updates a state and allows a user

to choose one of the theme colors provided by the Bootstrap CSS framework, which is then passed on to the container’s

children as a prop using those Top-Level APIs.

export function ThemeSelector( { children } ){

const themes = ["primary", "secondary", "success", "warning", "dark"];

const [theme, setTheme] = useState( 'primary' )

//handler for theme selection

const changeTheme = ( event ) => setTheme( event.target.value );

//iterate the passed children components with map and pass the additional prop to

// the cloned element

const childrenWithTheme = React.Children.map( children, child =>

React.cloneElement( child, { theme } ) )

return (

<div className="bg-dark p-2">

<div className="form-group text-left">

<label className="text-white">Theme:</label>

<select className="form-control" value={theme}

onChange={changeTheme}>

{themes.map( theme => <option key={theme} value={theme}>{theme}</option> )}

</select>

</div>

<div className="bg-info p-2">

{childrenWithTheme}

</div>

</div>

)

}

Because props are read-only, we can’t use the React.Children.forEach method to simply enumerate the child components

and assign a new property to their props object. Instead, I used the map method to enumerate the children and used

the React.cloneElement method to duplicate each child with an additional prop.

React.cloneElement(c, { theme: this.state.theme})

The cloneElement method accepts a child component and a props object, which is merged with the child component’s

existing props.

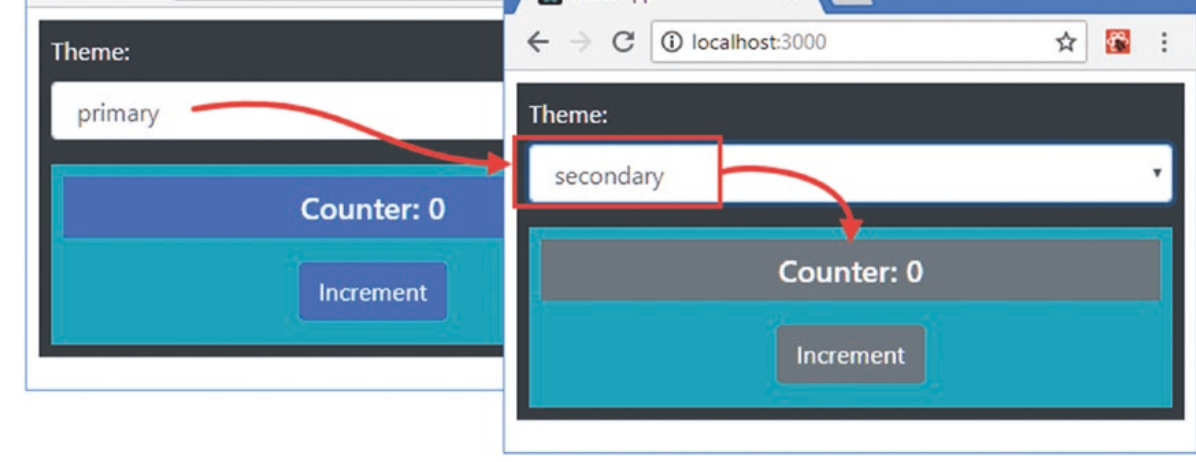

The result is that the props passed to the Message and ActionButton components are a combination of those defined by

the App component and those added using the cloneElement method by the ThemeSelector component. When you choose a

theme from the select element, an update is performed, and the selected theme is applied to the Message

and ActionButton components, as shown:

Exploring the container and presentational patterns#

There is a famous saying you hear everywhere in react community: You should avoid writing coupled components, your component should be reusable, and maintainable! but how?

One thinking that helps me to grasp that rule is that React components typically contain a mix of logic and ***

presentation***. By Logic I refer to anything that is unrelated to the UI, These are API calls, data manipulation,

heavy computations, and event handlers. The Presentation is the part inside render where we create the elements to

be displayed to the UI. In React, there are simple and powerful patterns, known as container and presentational,

which we can apply when creating components that help us to separate those two concerns. Let's see an example:

export default function CoolQuotes(){

const [quote, setQuote] = useState( { quote: '...loading' } );

useEffect( () => {

refreshQuote()

}, [] )

const refreshQuote = () => {

fetch( 'https://api.kanye.rest' )

.then( res => res.json() )

.then( setQuote )

}

return (

<div className='rounded bg-light mt-5 p-3 mx-4'>

<button className="btn btn-info" onClick={refreshQuote}>attach</button>

<p className='m-4'>

{quote.quote}

</p>

</div>

)

}

The above code give us:

In the above example am using a cool "API" by Andrew Jazbec that serves quotes of

Kanye. After the first render we send fetch request to 'https://api.kanye.rest', convert

the response to .json() and set the local state which then rerender the fetched data.

Now, this component does not have any problems, and it works as expected. But wouldn't it be nice to separate

the fetch logic from the part where the result is presented to make it clean? We will use the container and

presentational patterns to isolate the two.

The container knows everything about the logic of the component and is where the APIs are called. It also deals with data manipulation and event handling.

The presentational component is where the UI is defined, and it receives data in the form of props from the container. Since the presentational component is usually logic-free, we can create it as a functional, stateless component. There are no rules that say that the presentational component must not have a state (for example, it could keep a UI state inside it). Let's extract those two:

// inside CoolQuoteContainer.js

export const CoolQuoteContainer = () => {

const [quoteData, setQuoteData] = useState( { quote: '...loading' } );

useEffect( () => {

refreshQuote()

}, [] )

const refreshQuote = () => {

fetch( 'https://api.kanye.rest' )

.then( res => res.json() )

.then( setQuoteData )

}

return <CoolQuote quote={quoteData.quote} onRefresh={refreshQuote}/>;

}

//inside CoolQuote.js

export const CoolQuote = ( { quote, onRefresh } ) => {

return (

<div className='rounded bg-light mt-5 p-3 mx-4'>

<button className="btn btn-info" onClick={onRefresh}>attach</button>

<p className='m-4'> {quote} </p>

</div>

)

}

I renamed CoolQuote component to CoolQuoteContainer, this rule is not strict, but it is widely used in the React

community to append Container to the end of the Container component name and give the original name to the

presentational one.

As you can see in the preceding snippet, instead of creating the HTML elements inside the return of the container, we

just use the presentational one and pass the state (quote and onRefresh) to it.

Creating well-defined boundaries between logic and presentation not only makes components more reusable, but also provides many other benefits like,

- We can pass a dummy or placeholder data and put it in other places that need to display the same data structure,

- Other developers in our team can improve the container that uses the API by adding some error-handling logic, without affecting its presentation.

- They can even build a temporary presentational component just to display and debug data and then replace it with the real presentational component when it is ready.

What is the cue to use it?#

Applying this pattern without a real reason can give us the opposite problem and make the code base less useful as it involves the creation of more files and components. In general, the right path to follow is starting with a single component and splitting it only when the logic and the presentation become too coupled .

In our example, we began from a single component, and we realized that we could separate the API call from the markup. Deciding what to put in the container and what goes into the presentation is not always straightforward; the following points should help you make that decision:

The following are the characteristics of container components:

- They are more concerned with behavior.

- They render their presentational components.

- They make API calls and manipulate data.

- They define event handlers.

The following are the characteristics of presentational components:

- They are more concerned with the visual representation.

- They render the HTML markup (or other components).

- They receive data from the parents in the form of props.

- They are often written as stateless functional components.

Understanding HOCs( Higher Order Components )#

Conceptually, components are like JavaScript functions. They accept arbitrary inputs (called props) and return React

elements describing what should appear on the screen.

So, we can say that a component is a function of some data passed via props.

Therefore, we can continue this analogy with functions and extend it. What would

a Higher Order Component be?

Since a higher-order function either takes a function or returns a function or both,

we can assume that a higher-order component is one that takes a component and

returns another one as a result. This is what the official docs tell us.

HOCs are like higher-order functions but in the realm of React components. While a component transforms props

into UI, a higher-order component transforms a component into another component, enhanced in some way. They are a

literal implementation of a Decorator pattern.

const HoC = Component => EnhancedComponent

Let's add some additional functionality to the CoolQuote component to see HOC in action. If the user is a Pro

member, we enable the feature to see the author of the quote and will get nice background(see Bootstrap

class bg-info in side the withFetch hoc), if it's a logged-in user we want them able to share the tweet on Twitter.

Otherwise only attach the quote. Let's change the previous example to fit with HOC and we will go through it.

// changes inside CoolQuote.js, author and loggedIn are the additional props

export const CoolQuote = ( { quote, onRefresh, author, loggedIn } ) => {

return (

<div className='rounded mt-5 p-3'>

<button className="btn btn-info" onClick={onRefresh}>attach</button>

{loggedIn && <a className="btn btn-primary ml-2"

href={`https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=${quote}`}>

Tweet

</a>}

<p className='m-4'>" {quote} "</p>

{author && <span className='bg-light p-2'>Author --:

<i>{author}</i>

</span>}

</div>

)

}

Even though we added new functionality to it, we still keep the "dumbness"(if it's a word) of it, keeping the logic out of the presentation layer. This give use the following output:

// change made to the CoolQuoteContainer.js

export const CoolQuoteContainer = () => {

const [isLoggedIn,] = useState( true ); // login logic

const [isPro,] = useState( true ); //

const EnhancedCooQuote = withFetch( CoolQuote );

return (

<EnhancedCooQuote pro={isPro} loggedIn={isLoggedIn}/>

);

}

We take the fetching part into the HOC(we will see next) and let the container concern only be about user-logins and

pro member subscription logic and pass that logic state to the returned component from the HOC

like <EnhancedCooQuote pro={isPro} loggedIn={isLoggedIn} />, which will pass them again along with additional prop

to the intended(enhanced) component(see next).

The part we call the HOC like const EnhancedCooQuote = withFetch(CoolQuote); and rendering it passing props

like return <EnhancedCooQuote pro={isPro} loggedIn={isLoggedIn} /> was a little confusing. Remember after all HOCs

return a component we can pass props or render that component , and the props we passing is accessed inside that

component. Hope it make sense.

Let's see the HOC :

const withFetch = ( Component ) => {

return function( props ){

const [quote, setQuote] = useState( { quote: '...loading' } );

useEffect( () => {

refreshQuote()

}, [props] )

const refreshQuote = () => {

fetch( 'https://api.kanye.rest' )

.then( res => res.json() )

.then( setQuote )

}

return (

<div className={props.pro && 'bg-warning rounded'}>

<Component {...props}

author={props.pro && 'kayne west'}

quote={quote.quote}

onRefresh={refreshQuote}/>

</div>

);

}

}

We declare a withFetch function that takes a Component and returns another

function. The returned function is a functional component that receives some props and renders(wrap) the

original Component. The collected props are spread like <Component {...props}. We peeked inside incoming props to

include the author prop author={props.pro && 'Kayne west'}, we just map pro -> author, if a user is Pro then pass

the author other wise undefined. And also we add background color to the container for Pro users.

The reason why HOCs usually spread the props they receive on the component is because they tend to be transparent and

only add the new behavior. Pass unrelated props through to the wrapped component. I wrote nice blog

about spread operator

in this article.

The important part is we are also passing new, additional props author and onRefresh to the wrapped component and we

do not require the component to implement any function. This means that the component and the HOC are not coupled, and

they can both be reused across the application. Don't underestimate the power of props.

You may have spotted a pattern in the way HOCs are named. It is a common practice to prefix HOCs that provide some

information to the components they enhance using

the with pattern. Simply when you're thinking extending some component don't mutate the Original Component. Use

Composition(HOcs).

When to Use#

We can use HOCs when we need to share functionality between many components.

Injectors can extend the functionality of a given component by passing new props to

it. Sometimes HOCs are used for accessing network requests like the above, providing local storage access, subscribing

to event streams, or connecting components to an application store. The latter was used in the Redux library to connect

a component to the Reduxstore. These HOCs are often called providers but they work basically the same way.

Gochas#

We cannot wrap a component in HOC inside of render() (in runtime). React’s diffing algorithm uses component identity to determine whether it should update the existing subtree or throw it away and mount a new one. The problem here isn’t just about performance. Remounting a component causes the state of that component and all of its children to be lost. We must always apply HOCs outside the component definition so that the resulting component is created only once.

All the static methods if defined must be copied over.

There may be a situation when some props provided by a HOC have the same names as props from other HOCs or wrappers. The name collision can lead us to accidentally overridden props.

Making sense of FunctionAsChild.#

There is a pattern that is gaining traction within the React community, known as "FunctionAsChild". It is widely used in the popular react-motion and the form handling Formic libraries.

The main concept is that, instead of passing a child in the form of a component, we define a function that can receive

parameters from the parent. Let's see what it looks like: const FunctionAsChild = ({ children }) => children()

. FunctionAsChild is a component that has a children property defined as a function and, instead of being used as

a JSX expression, it gets called.

The preceding component can be used in the following way:

<FunctionAsChild>

{() => <div>Hello, World!</div>}

</FunctionAsChild>

Let's delve into an example where the parent component passes some

parameters to the children function. Create a Name component that expects a function as children and passes it a

string you want:

const Name = ( { children } ) => children( 'World' )

//which can be used like:

< Name >

{ name

=>

<div>Hello, {name}!</div>

}

</Name>

The snippet renders Hello, 'World!', but this time the name has been passed by the parent. It should be clear how this pattern works, so let's look at the advantages of this approach.

The first benefit is that we can wrap components, passing the variables at runtime rather than fixed properties, as we

do with HOCs.

A good example is a Fetch component that loads some data from an API endpoint and returns it to the children function:

<Fetch url="...">

{data => <List data={data}/>}

</Fetch>

Secondly, composing components with this approach does not force children to use some predefined prop names. Since the function receives variables, their names can be decided by the developers who use the component. That makes the FunctionAsChild solution more flexible.

Last but not least, the wrapper is highly reusable because it does not make any assumptions about children it

receives—it just expects a function. Due to this, the same FunctionAsChild component can be used in different parts of

the application, serving various children components.

Summary#

-

Props are a way to decouple components from each other and create a clean and well-defined interface

-

Container and Presentational pattern helped us to separate the logic from the presentation and create more specialized components with a single responsibility.